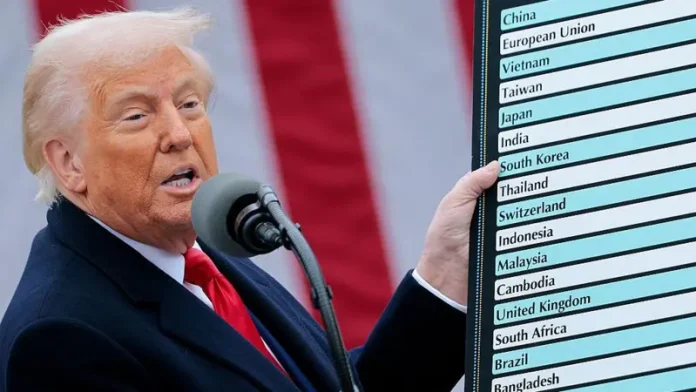

A new executive order from the United States government introduces a flat 15% tariff on most African exports, effective 7 August 2025, replacing earlier preferential rates extended under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). A few countries, including South Africa, Algeria, and Libya, face higher tariffs of 30%, with implications for manufacturing, agriculture, and export-oriented employment across the continent.

The tariff revision, part of a broader recalibration of U.S. trade policy, has placed African countries in a difficult position. Several economies had come to rely on preferential market access to the U.S. for specific export sectors. The new measures significantly increase the cost of entry for African goods and will test the resilience of local industries that had been geared toward that demand.

South Africa, for example, has warned that up to 30,000 jobs could be affected, particularly in automotive, agriculture, and textiles, as production geared toward the U.S. market becomes less competitive. Officials in Lesotho declared a national state of disaster after early signals of production closures and employment losses in the country’s garment sector.

While some tariff levels are lower than originally proposed earlier this year—Lesotho was initially facing a 50% rate, now reduced to 15%—the broader shift marks a departure from established trade arrangements. Africa Growth and Opportunity Act, first enacted in 2000, was never intended to be permanent, but the sudden, unilateral nature of this policy change has disrupted trade planning for several African countries.

Most affected African states had not diversified their export portfolios or trading partners substantially during the AGOA era. As a result, their current exposure to tariff shocks is high. Tunisia’s handicrafts sector, Botswana’s apparel exports, and Ghana’s fruit shipments are all vulnerable to reduced U.S. demand as importers face higher costs.

Even in more industrialised economies like South Africa, reliance on a small set of trade relationships—primarily with the U.S. and China—continues to limit flexibility in global markets. The government has announced new support measures, including working capital facilities, competition rule exemptions, and efforts to link exporters with new buyers through embassies and trade desks.

However, short-term relief does not address the underlying issue: African economies remain structurally dependent on a few external markets, often exporting raw or semi-processed goods with limited value addition.

The shift in U.S. trade policy also reflects broader tensions in global economic governance. Officials in Washington have tied the new tariffs to national security concerns and dissatisfaction with the foreign policy positions of certain African governments—particularly South Africa’s legal action against Israel and growing BRICS alignment.

This politicization of trade is not unique to the U.S., but it underscores Africa’s limited influence in settings where trade terms can be altered unilaterally by larger economies. It also raises questions about the effectiveness of bilateral trade negotiations when they are not anchored in long-term, rules-based frameworks.

As several African countries enter last-minute talks with U.S. officials, there is parallel interest in strengthening intra-African trade mechanisms, particularly through the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). However, the infrastructure, policy harmonization, and production capacity needed to make AfCFTA a viable alternative remain uneven across the continent.

In the immediate term, affected countries will need to reassess their trade risk exposure, engage in supply chain adjustments, and expand diplomatic efforts to secure stable, predictable market access in both traditional and emerging economies.

Longer-term, the lesson is clear: preferential access to major markets should not be the foundation of a national or regional trade strategy. Africa’s trade and industrial policy must now evolve to reduce reliance on external goodwill and instead focus on competitiveness, regional integration, and diversification of both products and partners.

Read also: Namibian summit sets model for youth inclusion in Africa’s energy industry