China will grant zero-tariff treatment to imports from 53 African countries from May 1, 2026, extending duty-free access to nearly the entire continent in a move that reshapes Africa’s external trade landscape at a time of shifting global alliances and renewed scrutiny of preferential market access. The decision, announced by Beijing over the weekend, excludes only Eswatini, which maintains diplomatic ties with Taiwan.

The policy broadens an existing preferential regime that had previously covered 33 African least developed countries (LDCs), where 97 to 100 per cent of tariff lines had already been eliminated. By expanding zero-duty access to almost all African economies with diplomatic relations with Beijing, China has effectively created the most comprehensive unilateral tariff concession framework currently available to African exporters among major trading partners.

Read also: Morocco doubles Avocado exports, surpasses Kenya amid Red Sea shipping disruptions

The announcement comes weeks after the United States moved to extend the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which provides selective duty-free access for eligible sub-Saharan African countries but remains subject to periodic renewal and compliance conditions.

The European Union’s Everything But Arms scheme offers full duty-free access only to LDCs, while non-LDC African countries must negotiate Economic Partnership Agreements to secure similar terms. Against this backdrop, Beijing’s decision consolidates its trade diplomacy across Africa at a moment when global supply chains and geopolitical alignments are under strain.

Trade between China and Africa has grown steadily, but structural imbalances persist. Data from China’s General Administration of Customs show that bilateral trade reached $222.05 billion between January and August 2025, up 15.4 per cent year on year.

Chinese exports to Africa rose 24.7 per cent to $140.79 billion, while imports from Africa increased by just 2.3 per cent to $81.25 billion over the same period. Africa’s trade deficit with China widened to $59.55 billion in eight months, nearly matching the $61.93 billion gap recorded for the whole of 2024.

The composition of trade explains much of the disparity. African exports to China remain concentrated in crude oil, copper, cobalt, iron ore and other mineral commodities. In 2023, mineral resources accounted for roughly 40 per cent of China’s imports from African LDCs, alongside non-edible raw materials and semi-processed goods.

By contrast, Chinese exports to Africa are dominated by machinery, electronics, vehicles and renewable energy equipment. Between July 2024 and June 2025, Africa imported more than 15,000 megawatts of Chinese solar panels, a 60 per cent increase on the previous 12 months, underscoring the depth of manufacturing asymmetry.

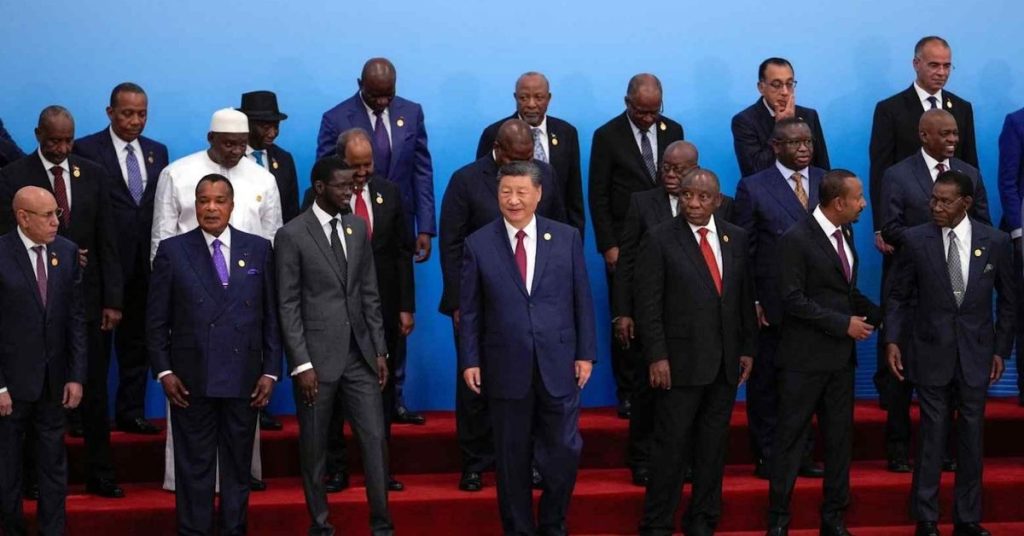

Beijing maintains that eliminating tariffs will support export growth from Africa and help narrow the imbalance. Economists estimate that China will forgo roughly $1.4 billion in tariff revenue annually under the expanded scheme. The fiscal trade-off is modest relative to overall trade volumes but significant as a signal of strategic positioning. The move aligns with commitments made under the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation and follows sustained engagement by African leaders seeking improved market access.

South Africa recently concluded a non-binding framework agreement with China under a Joint Economic and Trade Commission, paving the way for an Early Harvest Agreement that is expected to grant zero-tariff access for selected South African exports.

For African economies, the implications are tangible but conditional. Tariff elimination reduces a clear cost barrier, yet non-tariff constraints remain. Regulatory standards, quality certification requirements, logistics bottlenecks and limited access to trade finance continue to restrict the ability of many African firms to penetrate Asian markets. Export capacity is also constrained by low levels of industrial diversification. Without investment in processing, manufacturing and value addition, many countries risk expanding volumes of primary commodity exports rather than shifting into higher-value segments.

The policy therefore intersects directly with domestic industrial strategies. Countries pursuing agro-processing, textiles, automotive assembly or green manufacturing could leverage tariff-free access to scale exports if supply chains are competitive. Others may find that preferential access alone does not translate into market share gains. Much will depend on infrastructure systems, port efficiency, energy reliability and the ability of small and medium-sized enterprises to meet technical standards.

The zero-tariff regime also carries fiscal considerations within Africa. Greater export volumes can bolster foreign exchange earnings and strengthen external balances, particularly for economies under pressure from currency volatility and debt servicing costs. However, a widening trade deficit driven by continued import growth would offset such gains. Trade policy alone is unlikely to correct structural asymmetries without parallel reforms in productivity and industrial capacity.

China’s decision underscores a broader reconfiguration of Africa’s trade partnerships, where market access is increasingly intertwined with geopolitical alignment and development finance.

Engage with us on LinkedIn: Africa Sustainability Matters