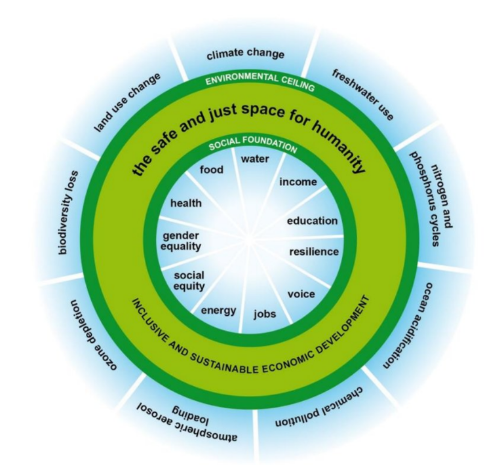

The operationalization of global sustainability frameworks across Africa is increasingly skewed toward ecological compliance at the expense of social stability, as institutions prioritize carbon budgets and biodiversity thresholds over fragile domestic foundations. While the “Doughnut Economics” model, pioneered by economist Kate Raworth, theoretically balances an inner social foundation of human well-being with an outer ecological ceiling of planetary limits, the practical application in African markets has become asymmetrical. According to recent data from the Federation of Kenya Employers, youth unemployment among those aged 15 to 34 remains a staggering 67%, highlighting a social foundation in a state of chronic deficit that risks being further undermined by technocratic environmental enforcement.

This imbalance is not merely a theoretical concern but a growing governance reality that manifests in land use and energy policy. In Kenya’s Mau Forest, the Ogiek indigenous community continues to contest state-led evictions framed as conservation efforts, despite repeated rulings from the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights ordering the government to recognize their ancestral land rights. Such cases underscore the risk of “eco-authoritarianism”, where environmental protection is used as a legal instrument for dispossession. According to legal analysts, if conservation limits land access without accompanying land tenure reform, the pursuit of an ecological ceiling directly collapses the social foundation of the communities most dependent on that land.

The fiscal implications for African sovereigns are equally severe. As global capital increasingly aligns with rigid ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) metrics, many African nations find that ecological metrics are more sophisticated and enforceable than social equity indicators. This creates a systemic pressure where countries are expected to meet stringent mitigation targets while still lacking the industrial policy required to generate employment for the one million young people entering the labor market in Kenya alone each year. According to the International Monetary Fund, the cost of climate adaptation in Sub-Saharan Africa could reach $50 billion annually by 2050, yet financing for the underlying social infrastructure, such as healthcare and skills development, frequently falls short of these figures.

Furthermore, the transition to renewable energy risks becoming an extractive rather than a distributive process if not grounded in local affordability. In many urban centers, informal labor accounts for nearly 89% of youth employment, a demographic that remains highly vulnerable to the inflationary pressures of energy transitions. Without benefit-sharing mechanisms and domestic value-addition policies, the expansion of green industries may serve global supply chains while leaving African households with high utility costs and stagnant wages.

Policymakers and development institutions are now being urged to move beyond “environmental reductionism.” A balanced sustainability agenda for Africa requires that institutional frameworks treat land rights, youth employment, and community governance as being as “non-negotiable” as carbon emissions targets. According to analysts at the World Economic Forum, Africa cannot afford a framework that prioritizes the planet at the expense of the person. If the regenerative goals of the 21st century are to be realized on the continent, the social foundation must be strengthened with the same precision and accountability currently reserved for the ecological ceiling.

Engage with us on LinkedIn: Africa Sustainability Matters