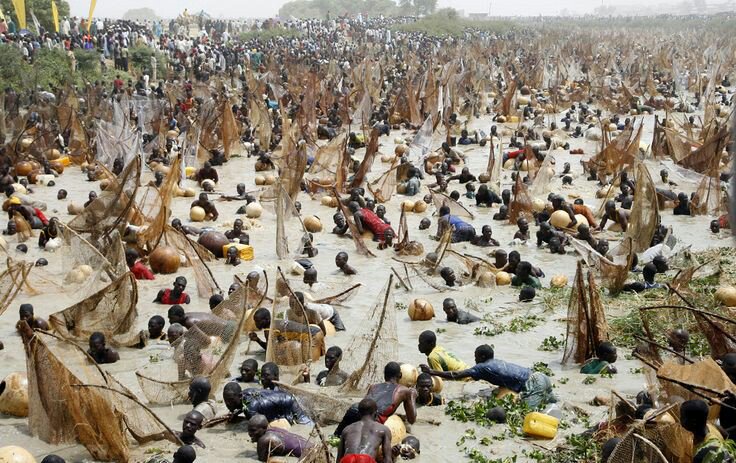

Thousands of fishermen surged into the shallow, silted waters of the Matan Fada River in northwest Nigeria on Saturday 14th February, as the Argungu International Fishing and Cultural Festival returned in full force in 2026, reviving one of West Africa’s most storied cultural gatherings after years of disruption. Spectators lined the riverbanks in Kebbi State, among them Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu with other dignitaries, as competitors armed with hand-woven nets, calabash gourds and bare hands wrestled for the season’s largest catch.

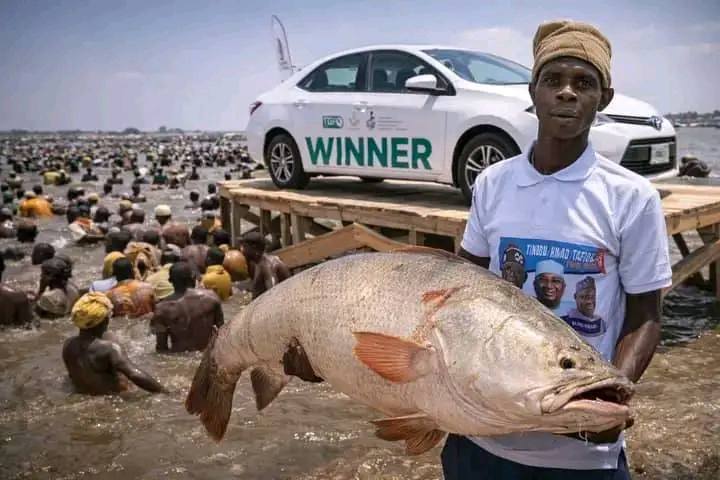

At stake was more than prize money. The winner hauled in a 59-kilogram croaker, earning cash and vehicles, while hundreds of smaller catches were sold in a temporary riverside market that injected short-term liquidity into the local economy. For many residents of Argungu town, the spectacle marked the restoration of a tradition first conceived in 1934 as a diplomatic gesture that ended decades of hostility between the Sokoto Caliphate and the Kebbi Kingdom.

The festival’s origins lie in a peace accord brokered between Sultan Hassan Dan Mu’azu of Sokoto and Muhammadu Sama, the ruler of Argungu. Fishing on the Matan Fada River, once contested territory, became an annual symbol of reconciliation. Over time, what began as a local peace ritual evolved into a national cultural asset, drawing visitors from across Nigeria and neighbouring Niger, Chad and Togo. Wrestling bouts, canoe regattas, archery contests and equestrian displays were added, transforming Argungu into a week-long celebration of Sahelian heritage.

Read also: South Africa’s small-scale fishers urge SAHRC to tackle food system inequality

The river itself is central to the ritual. It remains closed for most of the year under the custodianship of the Sarkin Ruwa, or water chief, to allow fish stocks to regenerate. On festival day, the ban is lifted for a single, tightly choreographed contest lasting barely an hour. The rules preserve pre-colonial fishing techniques, prohibiting modern gear and mechanised boats. The effect is both theatrical and conservation-minded, reinforcing communal stewardship of natural resources.

Argungu’s trajectory has mirrored Nigeria’s wider instability. The festival was suspended in 2010 amid deteriorating infrastructure and rising insecurity across the north, where Islamist insurgencies and armed criminal groups have displaced communities and strained state capacity. A brief revival in 2020 faltered as security concerns and the pandemic compounded organisational challenges. Organisers describe the 2026 edition as the first fully realised celebration in years, albeit under heightened security and with attendance below historic peaks.

For Kebbi State, the economic stakes are tangible. Agriculture and fishing underpin livelihoods in the region, and the festival traditionally signals the start of the dry-season economy. Hotels, transport operators and informal traders report a surge in demand during the event week. According to local officials, previous editions attracted tens of thousands of visitors, generating millions of naira in direct and indirect spending. In a region seeking to diversify beyond subsistence farming, cultural tourism offers a modest but symbolically important revenue stream.

The 2026 edition was held from February 10 to February 15, 2026, and extended well beyond its signature fishing contest, incorporating traditional wrestling finals, canoe regattas, polo at the NSK Polo Ranch, and a range of equestrian and martial showcases including camel and donkey races, horse riding displays and archery competitions, reinforcing Argungu’s status as one of West Africa’s most comprehensive cultural gatherings rooted in northern Nigeria’s Sahelian heritage.

President Tinubu framed the revival as evidence of returning stability for the country, though local leaders acknowledge lingering apprehension. “People are still cautious,” one organiser noted, citing sporadic attacks in parts of northern Nigeria in recent years. The visible presence of security forces around the river underscored both the risks and the state’s determination to project normalcy.

Beyond economics, Argungu carries political and environmental meaning. In a country often defined by ethnic and religious fault lines, the festival’s founding narrative, peace through shared resources, resonates anew. Its endurance suggests that cultural institutions can outlast political upheaval. At a time when climate variability is altering water flows across the Sahel, the ritualised closure and reopening of the Matan Fada River also highlight indigenous conservation practices that predate modern environmental policy.

Sustained security improvements and investment in infrastructure will determine whether the festival can reclaim its former scale. In reviving a 92-year-old peace ritual, Kebbi State has not merely staged a pageant. It has tested whether heritage can serve as economic stimulus and social glue in a fragile region.

Engage with us on LinkedIn: Africa Sustainability Matters