By Thomson Reuters

The

world’s food production is in jeopardy because the fertile layer of soil that

people depend on to plant crops is being eroded by human activities, scientists

said on Wednesday.

Climate

change is likely to make it worse even as demand from a grown population is

soaring, they said.

Soil

erosion happens naturally, but intensive agriculture, deforestation, mining and

urban sprawl accelerate it and can reduce crop yields by up to 50%, according

to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

FAO

also said the equivalent of a soccer pitch of soil is eroded every five

seconds, and the planet is on a path that could lead to the degradation of more

than 90% of all the Earth’s soils by 2050.

“We’re

approaching a critical point at which we need to start acting on soil erosion

or we are not going to be able to feed ourselves in the future,” Lindsay

Stringer, professor at England’s University of Leeds, said.

She

was speaking on the sidelines of a three-day conference on soil erosion

co-organized by the FAO.

Erosion

degrades soil, meaning it is less able to withstand stresses such as changes in

rainfall and longer droughts, Richard Cruse, professor at Iowa State University

in the United States, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

A

repeat of weather conditions like those experienced in 2012, including drought

and famine in the Horn of Africa and hurricanes in the United States,

“could really cut our food supply in a way that we haven’t

experienced,” he said.

Yet,

policy makers are too caught up in day-to-day issues to focus on soil erosion,

he added.

“They

have to deal with poverty, health, roads, things that are of immediate effect.

Soil erosion is long term. It’s like sands through an hourglass. We know what’s

happening, but we’ll worry about it tomorrow.”

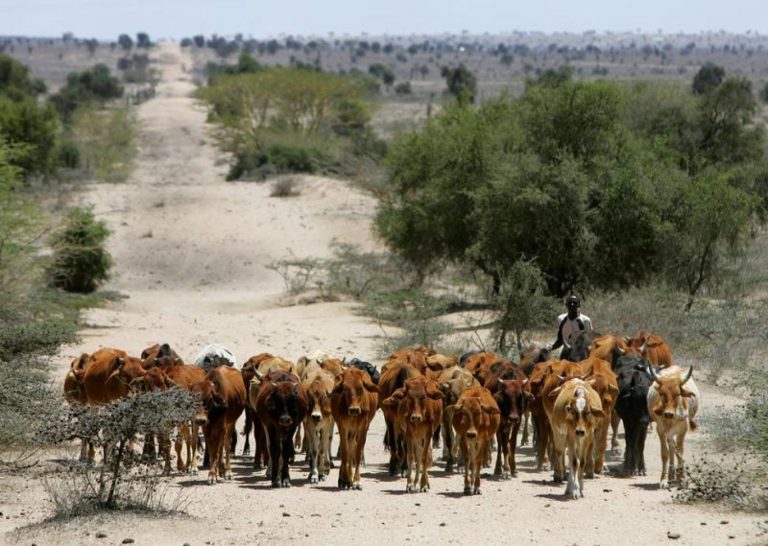

It

is not hopeless, said Stringer, whose research in Kenya found using manure as

fertilizer or growing more than one crop on the same plot of land are simple,

inexpensive actions that improve both soil quality and crop yield.

However,

other proven methods to reduce erosion, such as building terraces and engaging

in agroforestry – planting trees on cropland – can be too expensive for

farmers, she said.

Ownership

of land is key here, Cruse said.

“In

my conversation with farmers, they tell me, “If I own my own land and I’m

farming, conservation is an investment. If I have to use these practices on

rented land, it’s a cost.”

Governments

can give incentives to farmers through subsidies and other means, because good

soil benefits the wider society, while things would worsen if nothing is done,

said Jean Poesen from Belgium’s KU Leuven university.

“Ninety-five

percent of our foods come from soil. Can you imagine how the food section of a

supermarket would look like if we had no soils? There would be nothing on the

shelves,” he said.

“Once

the soil is gone… people end up with hard, bare rock, and nothing grows. Then

you have to migrate or start a fight with your neighbors and conquer.”

Read

original article on Thomson Reuters Foundation