Thermal power plants (heavy fuel oil/diesel/kerosene generators) in Kenya charge the highest in excess of $0.20 per unit of electricity produced and injected into the national grid.

This is four times more expensive than hydropower ($0.05) and slightly over twice the cost of geothermal ($0.08) and wind ($0.08) – the other main sources in Kenya’s energy mix. Besides being expensive, fossil-fuelled thermal plants emit greenhouse gases during generation, leaving a stain on the environment.

But beyond pricing and cleanness, thermal plants have over the years offered Kenya crucial backup as standby plants that swing into action at a moment’s notice during downtimes in geothermal and weather-dependent hydropower.

The diesel generators are flexible enough to be switched on and off and ramped up and down. This flexibility enables them to play a crucial role of matching demand spikes and drops in the national grid, acting as system stabilisers.

Due to their expensive power, which is tied to the cost of global fuel prices, diesel generators are only switched on after the rest of cheaper sources have been fully injected into the grid and their capacity has been exhausted, yet there’s still need for more power. This occurs mostly during peak demand in the evening from 6pm to 10pm when there’s an upsurge in consumption as people return home from work and schools, switching on lights and home appliances. This five-hour evening window is where thermal plants sneak into the national grid to meet the brief demand spurt before being shut down again as demand tapers off when homes sleep. Geothermal plants, though clean and cheap, suffer the drawback of not being flexible. They cannot be ramped up and down at a moment’s notice for load profiling while hydropower, though equally flexible like diesel generators and a good load profiler, is dependent on rain patterns.

Kenya has in recent years sharply cut the share of thermal plants in its generation mix while at the same time increasing geothermal, wind and solar production.

Currently, geothermal serves as a reliable baseload while hydropower stations, which are very flexible to adjust power output, are acting as spinning reserve for balancing out fluctuations in wind and solar sources. Thermal plants’ share is now below 10 percent compared to over 30 percent in 2013. But independent investors in thermal plants are still being paid capacity charges whether or not they generate electricity as stipulated in the power purchase agreements (PPA).

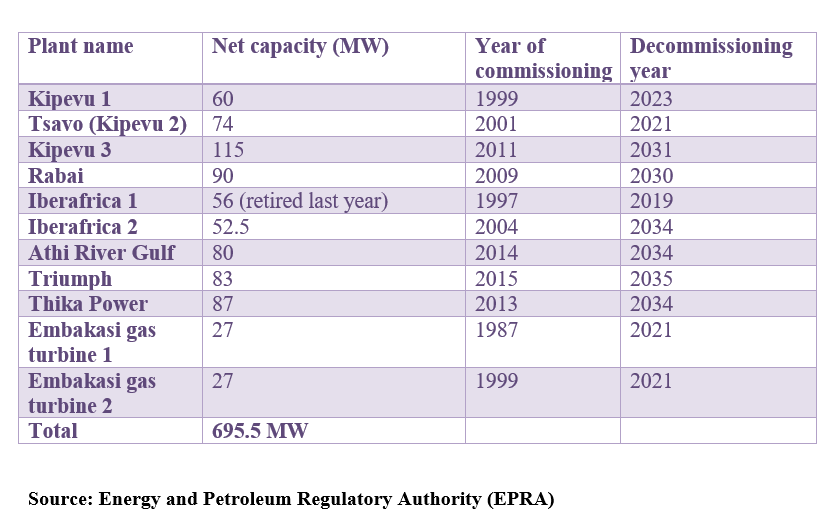

Below is the full list, along with details, of thermal power plants in Kenya

- Kipevu 1

Kipevu 1 power plant with a net capacity of 60 megawatts (MW) is located in Mombasa port city and was commissioned in 1999. It’s owned and operated by government-owned power producer KenGen.

The plant comprises six diesel engine generators manufactured by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries of Japan. The engines are rated at 12.5 MW each. However, over time, the engines have been derated to 10.4 MW each. The engines are fuelled with heavy fuel oil (HFO).

Launched in 1999, Kipevu 1 is due for decommissioning in 2023.

- Tsavo (Kipevu 2)

Tsavo diesel power plant (74MW) also known as Kipevu 2 is located directly next to Kipevu 1 plant in Mombasa, at Kenya’s coast. It’s owned and operated by independent power producer (IPP) Tsavo Power. It was commissioned in 2001 and is due for retirement in 2021, a 20-year lifespan.

The thermal power plant consists of seven diesel generators manufactured by Finnish firm Wartsila. The engines are fuelled by heavy fuel oil (HFO) to generate electricity.

- Kipevu 3

It’s the largest fossil-fuelled power plant in Kenya with a contracted effective capacity of 115 MW. It is owned and operated by KenGen and was commissioned in 2011.

The power plant comprises seven gensets manufactured by Finnish firm Wartsila, with a capacity of 17MW each. The engines are fuelled with heavy fuel oil (HFO).

Commissioned in 2011, Kipevu 3 is due for decommissioning in 2031, a 20-year lifespan.

- Rabai power plant

The 90MW thermal plant sits next to Kenya Power’s Rabai substation in the coastal county of Kilifi. The machine is operated and owned by Rabai power, an independent power producer (IPP).

It was commissioned in 2009 and is due for retirement in 2030

It consists of five diesel engines each with a capacity of 17MW and manufactured by Finnish company Wartsila.

To increase efficiency, the plant is equipped with a waste heat recovery system and a steam generator rated at 5 MW for optimal power output at a lower cost compared to other thermal power plants.

- Iberafrica power plant

The diesel-fired power plant is situated in Nairobi south and was previously owned and operated by Iberafrica Power before being recently acquired by Danish firm AP Moller Capital.

The first unit (56MW) was commissioned in 1997 and decommissioned last year (2019).

In 2004, the second unit with a net capacity of 52.5 MW kicked into operation and is due for decommissioning in 2034.

- Athi River Gulf

The 80MW diesel plant is located 25km south-east of Nairobi in Athi River. It was commissioned in October 2014 and is owned and operated by Gulf Energy, an independent power producer. Its decommissioning date is 2034, a lifespan of 20 years.

Its eight medium speed diesel engines are fuelled with heavy fuel oil.

Britam last year acquired an undisclosed stake in Gulf Energy via New York-based Everstrong Capital.

- Triumph

The 83MW diesel plant is located in Athi River (Kitengela) and is the most recent before the energy regulator put a moratorium on licensing any further thermal plants in 2015. It was commissioned in 2015 and has a lifespan of 20 years through to 2035.

The power plant consists of eight medium speed diesel engines.

- Thika power plant

The 87MW diesel plant was commissioned in second half of 2013 and is located in Thika, north east of the capital Nairobi.

The plant comprises five diesel engines as well as a waste heat recovery system and a steam generator, increasing its efficiency like with Rabai plant in the coastal town of Kilifi. It’s owned and operated by Thika Power, an independent power producer.

Commissioned in 2013, Thika diesel plant will be pulled off the grid for retirement in 2034.

- Embakasi power plant (partly relocated to Muhoroni)

The two gas turbines, each with a capacity of 27MW, were commissioned in 1987 and 1999 respectively. They’re owned and operated by KenGen.

Originally, the gas turbines were situated in Mombasa Kipevu area. However, out of the need to provide active and reactive power in the country’s main load centre, Nairobi, they were relocated to the city (Embakasi) in 2011. The gas turbines are fuelled with kerosene.

Due to the high short-run marginal costs, the Embakasi gas turbines were mainly used to provide peak load capacity.

Eventually in mid-2016, one gas turbine was relocated from Embakasi to Muhoroni in Kisumu to provide back-up capacity for western Kenya (replacing the 30 MW emergency power plant in Muhoroni operated by UK firm Aggreko).

- Aggreko Emergency power

With the objective to strengthen the power supply in western part of the country, electricity distributor Kenya Power contracted Aggreko to provide 30 MW rental power situated in Muhoroni.

The contract of the 30 MW Muhoroni rental power, which ran on speed diesel engines, expired mid-2016. It was effectively replaced by one gas turbine relocated from Embakasi to Muhoroni by KenGen.

Read also: Mini-grids to connect 110 million households to electricity

Engage with us on LinkedIn: Africa Sustainability Matters