The quiet scandal in corporate climate action is not the absence of targets. It is that much of the global food system’s climate ambition still rests on numbers that cannot be independently verified.

A recent press release by Koltiva, a Swiss-based agritech and supply-chain traceability company, draws attention to this fault line. It notes that agriculture and food systems account for nearly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet most of this footprint remains invisible at farm level. The company, which works with millions of smallholder producers to digitise and trace agricultural supply chains, argues that the credibility of corporate Net Zero commitments is being undermined by weak data from the very landscapes where emissions are generated.

According to the release, 82 per cent of corporate Net Zero targets remain unverified because companies lack reliable information on Scope 3 emissions and land-use change. Much of this gap lies beyond factory gates, in fields, grazing lands, and forest margins where production is informal, records are sparse, and monitoring systems are thin.

Read also: East Africa risks €2.75B in farm exports as EU traceability rules expose major compliance gap

On the ground, smallholder farmers across Africa are making daily production decisions under intense financial pressure, balancing household needs against rising input costs and uncertain yields. Many expand cultivation or cut back on inputs simply to keep their farms and families afloat. Taken together across millions of farms, these survival-driven choices quietly shape the global emissions profile of food, yet remain largely absent from corporate climate accounts.

For African agriculture, this problem is structural. The continent supplies cocoa, coffee, tea, palm oil, timber and livestock products to global markets that are now tightening sustainability rules. Yet most of this production is carried out by smallholders farming fragmented plots under complex tenure systems. Data on fertiliser use, soil management, energy inputs, or land conversion is rarely collected consistently, making precise carbon accounting difficult.

Deforestation illustrates the stakes. The Koltiva release cites data showing that roughly 75 per cent of global deforestation is driven by agricultural expansion. This aligns with assessments by organisations such as the World Resources Institute, which have linked commodity production to forest loss in West and Central Africa. In cocoa-growing regions of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, for example, incremental clearing has become a survival strategy for farmers facing declining yields and rising costs.

However corporate reporting often treats land-use emissions as abstract risk categories rather than geographically specific realities. Many companies still rely on aggregated estimates, leaving blind spots around where clearing happens, why it occurs, and who benefits from it.

This matters because regulatory pressure is intensifying. Under the European Union’s Deforestation Regulation and Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, companies must demonstrate that products are not linked to recent forest loss and that emissions claims are backed by evidence. According to European Commission guidance, operators are now expected to provide plot-level geolocation data for key commodities.

For African exporters, this represents both opportunity and danger. Verified low-deforestation, low-emissions production can protect access to premium markets. But producers who cannot document their practices risk exclusion, regardless of their actual environmental performance.

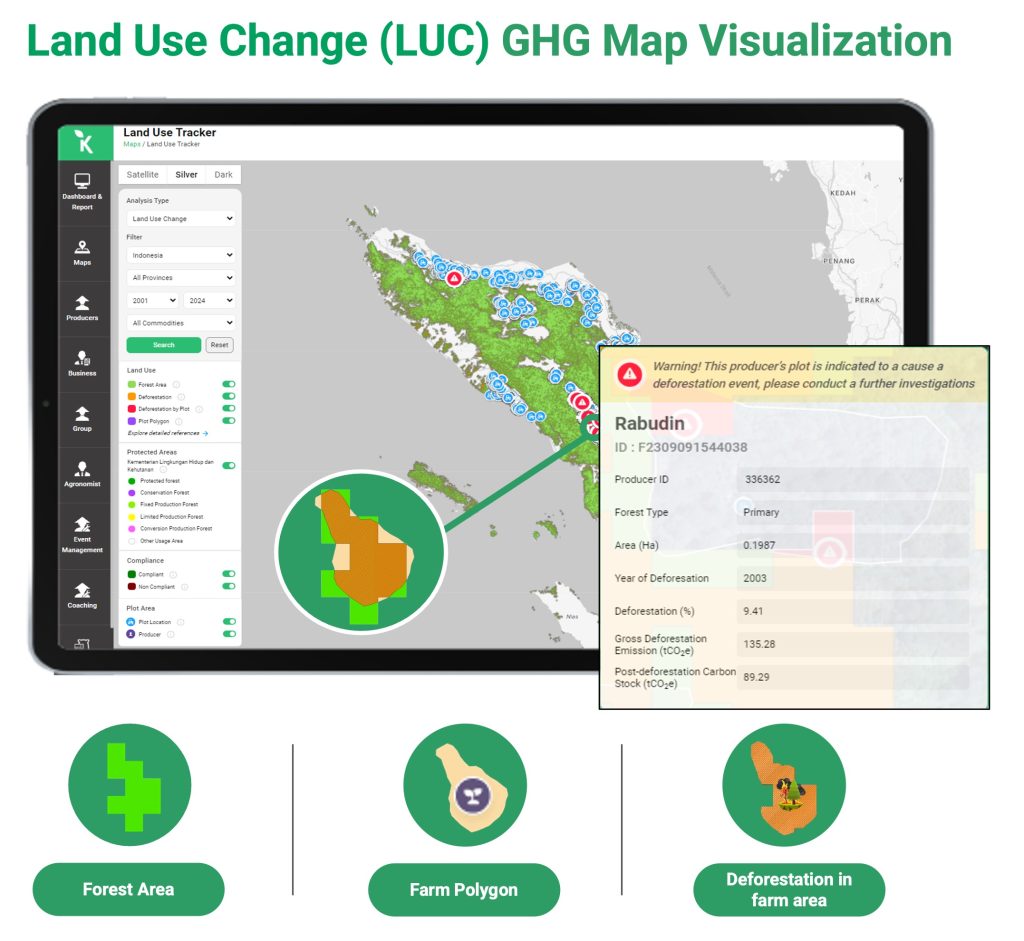

Koltiva’s response to this dilemma centres on combining satellite monitoring with verified field-level data. Its platforms integrate geospatial imagery with information on farming practices, fertiliser application, livestock management, and land use. The aim, according to the company, is to move from broad estimates to auditable, decision-ready emissions data.

Read also: Corporate climate targets go mainstream as 10,000 companies win SBTi validation

This “ground-truthing” approach reflects a growing consensus in climate accounting. Satellites can detect canopy loss or vegetation stress, but they cannot explain the practices behind those patterns. Linking remote sensing to structured, on-the-ground data is what allows emissions figures to withstand scrutiny from regulators, investors, and buyers.

However, building such systems is neither simple nor cheap. It requires trained field staff, digital infrastructure, repeated farmer engagement, and robust data governance. In many rural African regions, weak connectivity and limited extension services remain major constraints. According to the GSMA, nearly half of rural Africans still lack mobile internet access.

The financing question is therefore central. The Koltiva release links credible emissions data to investor confidence, regulatory compliance, and market resilience. But development institutions such as the African Development Bank have warned that “green compliance costs” could become a new barrier for small exporters unless concessional finance and blended funding are scaled up.

The deeper issue is how Scope 3 emissions are understood. In many boardrooms, they remain a reporting headache. In agricultural supply chains, they are where transformation must happen: in how land is managed, how soils are nourished, how forests are protected, and how yields are raised without expanding into new land.

The Koltiva release underscores this point, noting that without reliable, interoperable farm-level data, companies struggle to identify hotspots, deploy targeted interventions, or meet climate commitments. As standards such as the Science Based Targets initiative’s FLAG guidance and ISO 14068 tighten scrutiny of carbon claims, vague assurances are becoming harder to sustain.

The credibility crisis in food-sector climate action is not, at its core, about technology. It is about whether transparency becomes a pathway to shared value or another filter that decides who stays in global markets.

As pressure grows for companies to prove real progress, the farms of Africa are no longer peripheral to climate governance. They are where credibility will be won or lost.

Engage with us on LinkedIn: Africa Sustainability Matters